Today, I’d like to give an introduction to another area of concentration, the abdominals. Your deepest layer of abdominals (the muscles closest to the skeleton) are the transverse abdominals. This set of abdominals acts as a corset that wraps all the way around the torso. The transverse muscle blends into the lumbodorsal fascia which attaches into the lumbar spine. When the transverse muscle contracts, it pulls to the sides and stretches across the front of the pelvis because the fascial connections around the lumbar spine contract, essentially acting as a corset and decreasing the diameter of the waist.

Today, I’d like to give an introduction to another area of concentration, the abdominals. Your deepest layer of abdominals (the muscles closest to the skeleton) are the transverse abdominals. This set of abdominals acts as a corset that wraps all the way around the torso. The transverse muscle blends into the lumbodorsal fascia which attaches into the lumbar spine. When the transverse muscle contracts, it pulls to the sides and stretches across the front of the pelvis because the fascial connections around the lumbar spine contract, essentially acting as a corset and decreasing the diameter of the waist.

The transverse not only flattens the belly but helps to protect and strengthen the lower back. The transverse is one of the core muscles that we always hear about when talking about Pilates. A core muscle acts to stabilize and align the skeleton. With a certain amount of discipline, the core muscles can be trained to fire at all times. So when we are ready to go into the bigger movements such as jumping, squatting, and running, the skeleton is stabilized and protected.

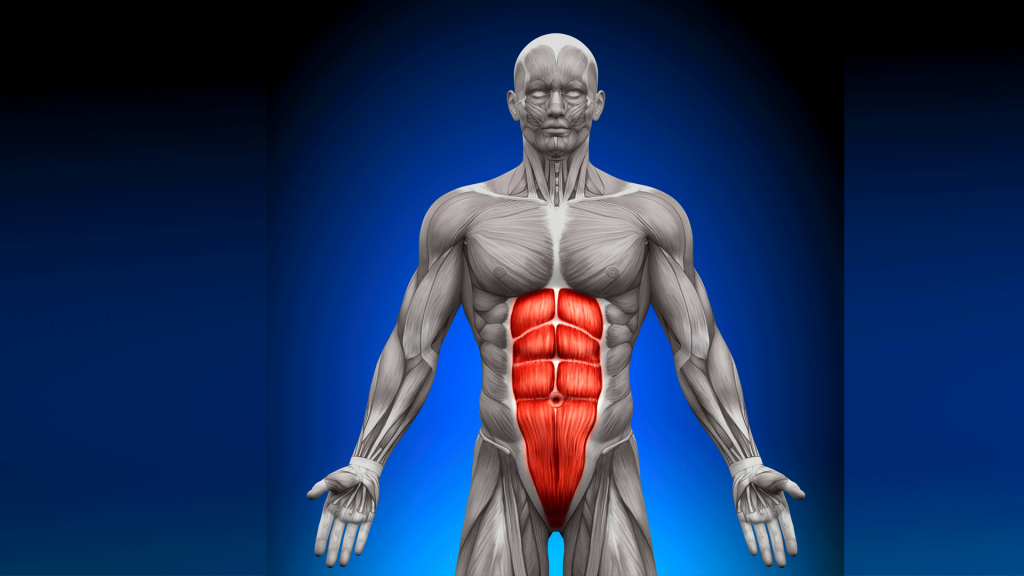

Abdominal strength starts with the core, but the core does not move the torso. To create movement, the remaining abdominals must be engaged. These muscles are the rectus abdominis, internal oblique abdominals, and the external oblique abdominals.

The rectus abdominals are the muscles we refer to as the six pack muscles. They are split into left and right halves and run vertically down the front of the torso. They attach into the transverse abdominals near the pubic bone. This set of muscles are surface muscles (not core) and help us to create movement – primarily flexion in the torso. In many circumstances, people concentrate on training the rectus muscles without the support of the transverse abdominals, which does not create the effect we’re all working toward. The abdominals will never flatten and often, a split of two fingers or more will be created between the halves of the rectus, called a diastisis. This splitting is also very prevalent in pregnant or postpartum women. When a diastisis occurs, intestines will often bulge out of the gap of and put the lower back in jeopardy. The only way to close the gap is through strengthening the transverse without stressing the rectus or with surgery.

The other two sets of abdominal muscles are the internal and external obliques. The perception is that working these muscles will give us a small waist, but this is not the case. If we work the rectus and obliques without working or firing the transverse, we will end up with a boxy, distended look. The key to achieving an hourglass figure (small waist line) is through our corset muscle – the transverse abdominals. The obliques definitely help to enhance the work if the transverse is engaged as well. We have two sets of obliques. The internal obliques, also referred to as same side rotators, lie just above the transverse abs and under the external obliques. We contract these muscles to rotate and to perform side bends of the trunk to the same side. The external obliques act as opposite side rotators. For example, when we rotate to the left, our internal abs on the left and external abs on the right are contracting.

At this point, I would also like to review the neutral spine and pelvic position. According to current research in biomechanics, the core or inner-unit works best as a spinal stabilizer when the pelvis is in a neutral position. Understanding the neutral spine and pelvis is absolutely essential to effectively work the abdominals.

The placement of the pelvis is considered to be neutral when the anterior superior iliac spines (front hip bone) and the pubic bone are in a plane perpendicular to the ground in standing or sitting and parallel to the ground when supine. In our ab work, we will be coming into and out of the neutral spine and pelvis position. It is easiest to find a neutral spine/pelvis by standing against the wall or lying on your back. You must be aware of the following three anchors:

• The backside of the sacrum (S-2) and pelvis

• The backside of the solar plexus (T-8)

• The base of the head (occipital base)

If your upper and/or lower back is too arched or too rounded to get you into the proper neutral position, you may need to pillow the head forward to find the proper head alignment, mid-back connection, and placement of the pelvis.

Follow these tips to help you find your neutral spine and pelvis. Again, this is essential as a base for working our abdominals.

• Lie on your back with the knees bent and the feet on the mat spread hip distance apart.

• Keep the middle of the back of the head and the mid-back (bra line) anchored to the floor.

• Bring the heels of the hands (the bottom of the palm close to the wrist) to the hip bones on the front of the pelvis and the fingertips on the pubic bone.

The spine and pelvis are neutral if you have your upper anchors (middle of the back of the head and mid-back) and the heels of the hands and fingers are on the same plane. If the fingers are above the heels of the hands, then the pelvis is in a posterior tilt with the tailbone reaching toward the ceiling. If the fingers are below the heels of the hands, then the pelvis is in an anterior tilt with the tailbone reaching to the mat and the ribcage popping to the ceiling.

Both of these two scenarios are extreme positions of the pelvis. You are looking for the middle ground between these two extremes.

Hope you enjoyed the article. Give me some feedback below!

~ by Jennifer Gianni

Leave A Reply (5 comments So Far)

Please - comments only. All Pilates questions should be asked in the Forum. All support questions should be asked at Support.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I love this concise, yet detailed explanation!

Jen is so great at explaining anatomy! Love it!

Great review of the abdominals!

This is so concise and succinct—thank you!

Thank you all so much for your feedback!

Love

Jen